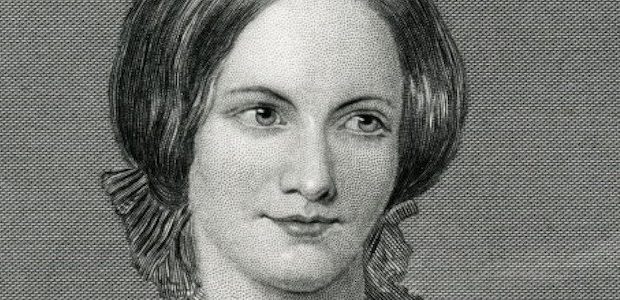

Rachel Savage, a second year History student at the University of Portsmouth, has written the following blog entry on letters sent between author Charlotte Brontë and her friend Ellen Nussey, for the Introduction to Historical Research module. Rachel reveals how personal sources like this can be used to gain insight into the emotions of women living in the 19th century Britain. The module is co-ordinated by Dr Maria Cannon, Lecturer in Early Modern History at Portsmouth.

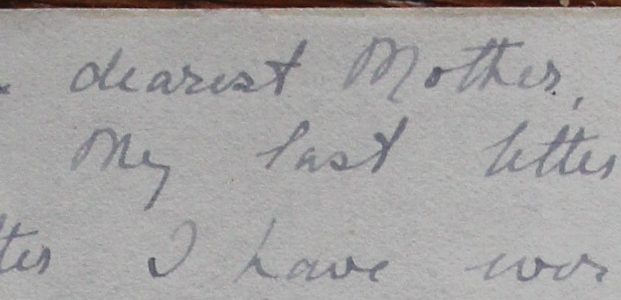

Charlotte Brontё was born in 1816 and grew up in a society which compelled her to conceal her gender with the pseudonym Currer Bell in order to initiate her successful writing career. [1] The suppressive lives women experienced in the Victorian period led Charlotte to form a close relationship with Ellen Nussey. [2] It is the closeness of this relationship that will be explored in this blog, as some historians, such as Rebecca Jennings, believe their relationship to have been a romantic one. [3] The primary sources used to debate this question are two letters that Charlotte wrote to Ellen in 1836 and 1837. [4] The analysis of these letters is crucial to this question and the extent to which these letters are useful as a piece of historical research will also be discussed.

It is evident from these letters that Charlotte cared greatly for Ellen as there is an abundance of emotive language which expresses Charlotte’s honest feelings, for example, “what shall I do without you?”, and “I long to be with you.” [5] Rachel Fuchs and Victoria Thompson argue that these expressions are not evidence of a romantic relationship, as in this time period women would form very close bonds and their letters would contain the topics of “their joys, their loves and their bodies.” [6] Therefore, the intimate nature of these letters may be evidence of how two friends felt they could truly be honest with each other rather than being evidence of a romantic relationship. However, it is interesting to consider that Charlotte herself was concerned that her letters to Ellen were too passionate and might be condemned. [7] This suggests that their relationship was a romantic one. Arguably one of the most passionate sentences in the 1837 letter – “we are in danger of loving each other too well” – could suggest that Charlotte and Ellen were on the brink of a romantic relationship and were in fear of that relationship developing. Because Victorian women were expected to have no sexual desires, the idea that two women could be having a romantic relationship was completely unacceptable to society. [8] Thus, Charlotte and Ellen may have feared the consequences of a romantic relationship developing.

These letters further highlight the context of Victorian society in which men were perceived to be superior. This limited the possibility of Ellen and Charlotte ever living together, most clearly captured in the lines, “Ellen I wish I could live with you always”, and “we might live and love on till Death without being dependent on any third person for happiness.” [9] Here Charlotte refers to a third person being a man, as in Victorian society women were completely dependent on men economically as they were the sole earners and therefore for women in a same-sex romantic relationship they faced economic barriers when it came to establishing a home together. [10] Consequently, for “novelist Charlotte Brontё and her lifelong romantic friend, Ellen Nussey, a joint home remained an unattainable dream.” [11] The fact that Charlotte and Ellen desired to live with one another suggests a romantic nature to their relationship. This is further emphasised when Ellen’s brother Henry proposed to Charlotte in 1839; Charlotte considered accepting in order to live with Ellen, but ultimately she could not accept the proposal. [12] The mere fact that Charlotte considered the proposal suggests her immense desire to live with Ellen, although as she writes in her 1836 letter that she wanted to live with Ellen without the dependence of a third person. Subsequently, this may have led her to decline the proposal. [13] As well as this, Jennings suggests women feared “that marriage would limit their independence further and restrict their access to their female friends.” [14] This was certainly the case for Charlotte when she married Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1854, as he prevented Charlotte and Ellen meeting on occasions and he read all of Charlotte’s letters before she sent them to Ellen. [15] Furthermore, the significance of Charlotte rejecting Henry’s proposal in 1839 suggests that the desire to live with Ellen in 1836 was still a dream to which Charlotte clung.

It is also important to illuminate the positives and limitations of using these letters to gain a true historical representation of Charlotte Brontё. The use of letters for historical research is helpful because, as Miriam Dobson suggests, they offer a true representation of the authors feelings. [16] It is unlikely that Charlotte would have been dishonest with Ellen especially as they had such a close relationship, whether it be romantic or not. However, Alistair Thomson argues that “every source is constructed and [a] selective representation of experience.” [17] Subsequently, although Charlotte is likely to be honest within this source she would also have been selective in what she wrote. This is especially significant to these letters. If Charlotte did have a romantic relationship with Ellen, she had to be careful how explicitly she expressed her love for her, for if someone other than Ellen had read these letters they could both face social exclusion from society. It is this selectivity that causes historians such as Jennings, Fuchs and Thompson to debate whether Charlotte and Ellen actually had a romantic relationship. Although, these letters offer a clear insight into the personal life of Charlotte Brontё and her thoughts and feelings, it is also important to remember that letters are a response to a previous interaction. [18] Consequently, these letters cannot be considered in isolation, as Ellen’s responses are also important to the creation of Charlotte’s image and presentation of herself.

In summary, by considering these letters historians can gain a deeper insight into the personal relations that Charlotte had and how she constructed her self-image to Ellen with the influence and constraints placed on her in society in which she could not openly express her love for Ellen. It is certainly clear that Charlotte would be honest and express her deepest thoughts and desires with Ellen. The question of Charlotte’s lesbianism is in no way conclusive, as more letters would need to be analysed especially those by Ellen. However, it is likely they may have desired a lesbian relationship, but the social constraints were too restricting to do so.

Notes

[1] Dinah Birch, “Charlotte Brontë”, in The Brontёs in Context ed. Marianne Thormählen. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 65.

[2] Eugene Charlton Black, “Sexual Roles: Victorian Progress?”, in Victorian Culture and Society ed. Eugene Charlton Black. (London: Macmillan, 1973), 385.

[3] Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain: Love and Sex between Women Since 1500 (Oxford: Greenwood World, 2007), 51.

[4] Charlotte Brontё, “C.Brontё letters to Ellen Nussey, 1836”Alison Oram and Annmarie Turnbull, The Lesbian History Sourcebook: Love and Sex Between Women in Britain from 1780-1970 (New York: Routledge, 2001), 60-61.

[5] Brontë, “C. Brontë”, 61.

[6] Rachel G. Fuchs and Victoria E. Thompson, Women in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 38.

[7] Jennings, Lesbian, 53.

[8] Fuchs and Thompson, Women, 40-41.

[9] Brontë, “C. Brontë”, 61.

[10] Jennings, Lesbian, 51.

[11] Jennings, Lesbian, 51-52.

[12] Jennings, Lesbian, 53.

[13] Brontë, “C. Brontë”, 61.

[14] Jennings, Lesbian, 53.

[15] Jennings, Lesbian, 53-54.

[16] Miriam Dobson, “Letters”, in Reading Primary Sources: The Interpretation of Texts from Nineteenth and Twentieth Century History ed. Miriam Dobson and Benjamin Ziemann. (New York: Routledge, 2009), 60.

[17] Alistair Thomson, “Life Stories and Historical Analysis”, in Research Methods for History ed. Lucy Faire and Simon Gunn. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), 102.

[18] Dobson, “Letters”, 69